Introduction

Higher education at a university is a crucial part of a student’s life because of the immense impact it may have on their future. Professors shape a huge portion of students’ college experiences; in addition to their standard roles as educators, at times they also act as mentors, role models, and even friends. The professor is entirely dominant in a student-professor relationship, despite some professors not even knowing the names of their students, allowing their teaching to affect the student interminably. University professors work toward making their students interested and proficient in a specific topic, shaping their understanding and associated careers. Furthermore, degrees from universities increase opportunities and provide a sound foundation for a student to secure a job in their chosen field of study.

Unfortunately, bias and stereotypes that shape behaviors and actions are present in the teachings of all educators. People can have implicit bias, which “occurs automatically and unintentionally, that nevertheless affects judgments, decisions, and behaviors” (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). One example is teachers favoring students of a particular race, ethnicity, or gender by grading them differently. Other times, bias can be obvious. Explicit bias includes things such as openly holding prejudices against one group of people. With the power and influence professors and their teachings hold over students, their biases can easily be projected onto students. Each student experiences the world differently, so the interpretation of teachers’ biases may vary from student to student, which is known as symbolic interactionism. However, the potential for influence remains the same. At a younger age bias affects students’ growth and behavior, but at the university level bias may affect their ability to be open-minded or even to succeed in their upcoming careers.

While any form of bias can be harmful, gender bias has a prevalent impact on female students, especially in male-dominated or formerly male-dominated university departments such as political science. Only 27% of tenure-track faculty and Ph.D. Students in political science are women, and popular political science journals publish females about ¼ of the time (Hinze, 2023). Additionally, in a survey of over 1,000 females from political science departments, students, and faculty, 43% believed their gender affected their standing in the department negatively (Hinze, 2023). Gender bias is favoring or holding prejudices against people because of their gender. It creates and enables many stereotypes that have heavily influenced many cultures and restricted specific genders to certain roles. In the classroom, gender bias can go both ways - professors can have gender bias against students and students can have gender bias against professors. For this paper, I will focus solely on the impact of professors’ gender bias on their students, which may come in the form of grading differences based on gender rather than performance, general favoritism, or emphasizing certain parts of the curriculum and leaving out others. Based on the knowledge discussed below on bias, there is a likelihood of gender bias being present in an overwhelming one-gender department (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). Revisiting symbolic interactionism, students are all experiencing this bias from different perspectives, causing it to affect each one differently.

After discussing the most recent published literature on the topic in the literature review, the rest of the paper explores how gender representation in U.S. political science departments relates to female students’ career paths. To understand this relationship, I will analyze data on the gender makeup of political science departments throughout the United States and I will discuss what general fields graduates go into following the completion of their degrees. I will then use this data to demonstrate the gap in female and male representation in the top three career paths for political science majors. Lastly, I will identify the type of relationship this is and how it is important for addressing the issue.

Literature Review

To determine if there is a correlation between the bias of a political science university professor’s teachings and their students’ careers, the bias first must be identified. According to researcher Dr. Cheryl Staats, bias is a serious form of prejudice, and it is prevalent in classrooms today (2015). Implicit and explicit bias is created due to the separation of our minds into two systems, with System 1 making unconscious, fast decisions and System 2 making thoughtful, slow decisions. System 1 controls implicit biases and the rapid conclusions it draws make it difficult for us to identify when we decide with bias. Educators are commonly pressed for time, forcing them to come to a verdict on issues quickly. This speed activates System 1 and leads them to unknowingly project bias through simple decisions. Staats demonstrated how impactful implicit bias can be on students by reviewing a 2010 study on bias’s effect on educator expectations. The research team found that implicit bias shaped teachers’ expectations of ethnically different students despite a teacher’s explicit goals for the class, such as expecting lower quality writing from students of color and thus leading them to be evaluated and graded lower (Staats, 2015). The detrimental effects on students shown in this study translate at the collegiate level such as students not being given full credit for work, not being provided with the same opportunities because of belief they will not take advantage of them, or students being graded differently due to implicit expectations that certain groups will perform lower.

Diving deeper into the potential impacts of implicit bias, another researcher, Dr. Skov reviewed how unconscious bias can be gender related in academia. He wrote that due to implicit bias being present in every person, it is not omitted from the classroom either. Therefore, bias unknowingly shapes teachers’ actions and opens the door for discrimination, which can lead to larger issues such as racial or gender inequity in the classroom or later in the workplace. Upon collecting 54 publications and analyzing their data for implicit gender bias, Dr. Skov found that 36 publications provided evidence that there is bias affecting women in academia (2020). When discussing the diverse ways evidence could point to the same conclusion in the publications, Dr. Skov also reiterated the importance of understanding that researchers can project implicit bias in numerous forms, such as making assumptions, spreading misinformation, or exaggerating data. Dr. Skov concluded that gender gaps in academic careers are a result of implicit bias in the classroom (2020). This evidence suggests that implicit bias based on gender can have an impact on careers overall.

The previous two papers established what gender-based implicit bias is and its potential effects on the students’ careers. However, it is even more important to analyze how this bias is being transferred to determine if it does have effects on students. The learned behaviors or associations people make from repeated interactions with someone are called symbolic interactionism, and researchers have demonstrated how those interactions generate symbols to help our minds establish connections and pick up habits from others (Carter & Fuller, 2015). In a classroom, professors may have repetitive teaching patterns that contain bias, so the repeated exposure to these practices is symbolic interactionism transferring gender bias from professors to students. The authors also pulled from the concept of “doing gender,” which says that roles different genders are given come from human interaction (Carter & Fuller, 2015). Within interactions, the people in power, professors, can influence the normality in their small setting, enabling the “doing gender” construction and thus reinforcing stereotypes that have the potential to impact students later in life.

Finally, when writing about her own experiences as a former student, now professor, Dr. Lynda Powell drew the specific connection that gender bias exists in academia and can and does affect the careers of students. Dr. Powell went to a predominantly female university and taught there after graduating. Despite the university having a larger female representation overall, the university’s student-led academic journal had the third lowest female membership. This disparity led her to investigate a possible correlation between bias from professors to former students in their careers - in this case, graduates in journalism. Dr. Powell interviewed female students to gather qualitative data on gender dynamics in their journal section. Additionally, this paper pulled quantitative data on each section’s publishing rates by gender to review the difference. Compiling the qualitative and quantitative data together, Dr. Powell presented compelling evidence for a correlation between professors’ biases, despite a large number of them being female, and female students’ decisions to pursue journalism after graduation. This study showcased the possibility for this correlation to be a relevant factor across other departments at the collegiate level, affecting the trajectories of students’ careers (Powell, 2020).

These sources provide a foundation for the data I will later review by establishing basic information on how bias is presented, what gender bias is, how it is projected, and how it affects those it is being projected on. Understanding the difference between implicit and explicit bias is vital to this research, as it allows one to comprehend how someone can be transferring bias to others without intention. It is important to know the synergies of those variations in bias with symbolic interactionism, as it is the method by which the transfer is possible. Dr. Powell’s findings and research strengthen my argument as they present a real-world example of how symbolic interactionism, implicit bias, and explicit bias all contribute to the projection of gender bias in the classroom. The literature review suggests that the connection between implicit/explicit bias, symbolic interaction, and personal experience all lend a hand in applying this correlation specifically to U.S. university political science departments.

Methods

This is a quantitative study of how gender biases, rooted in discrepancies in representation, can affect female students’ career choices. I analyze the correlation between underrepresentation in universities and fewer women choosing to continue in political science careers. The goal of this project is to understand if the lack of female representation in political science departments in universities impacts the trajectories of female student’s careers. Looking at the gender makeup of universities overall, political science professors and political science students will assist in my analysis of how demographics influence or change in different environments. Additionally, I analyze data on political science professors’ gender ratios over time. Following that, I examine the top three career paths that political science students tend to take – government, law, and business – and the gender makeup of each of those careers (Cal State LA, 2023). This data was pulled from credible sources found online, such as academic journals, reports from UN Women, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics amongst others.

I correlate that as implicit bias increases, a woman’s likelihood of continuing a career in political science decreases due to educators, department bias, and demographic makeup. I hypothesize that the underrepresentation of females in political science university departments discourages female political science students from continuing in a related profession later in life. This paper identifies the issue of implicit bias due to discrepancies in gender representation in the political science department’s faculty in universities. A correlation between this bias and the lack of females in political science careers was established.

Results

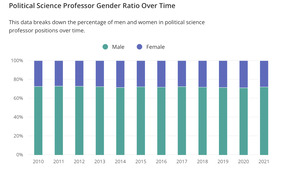

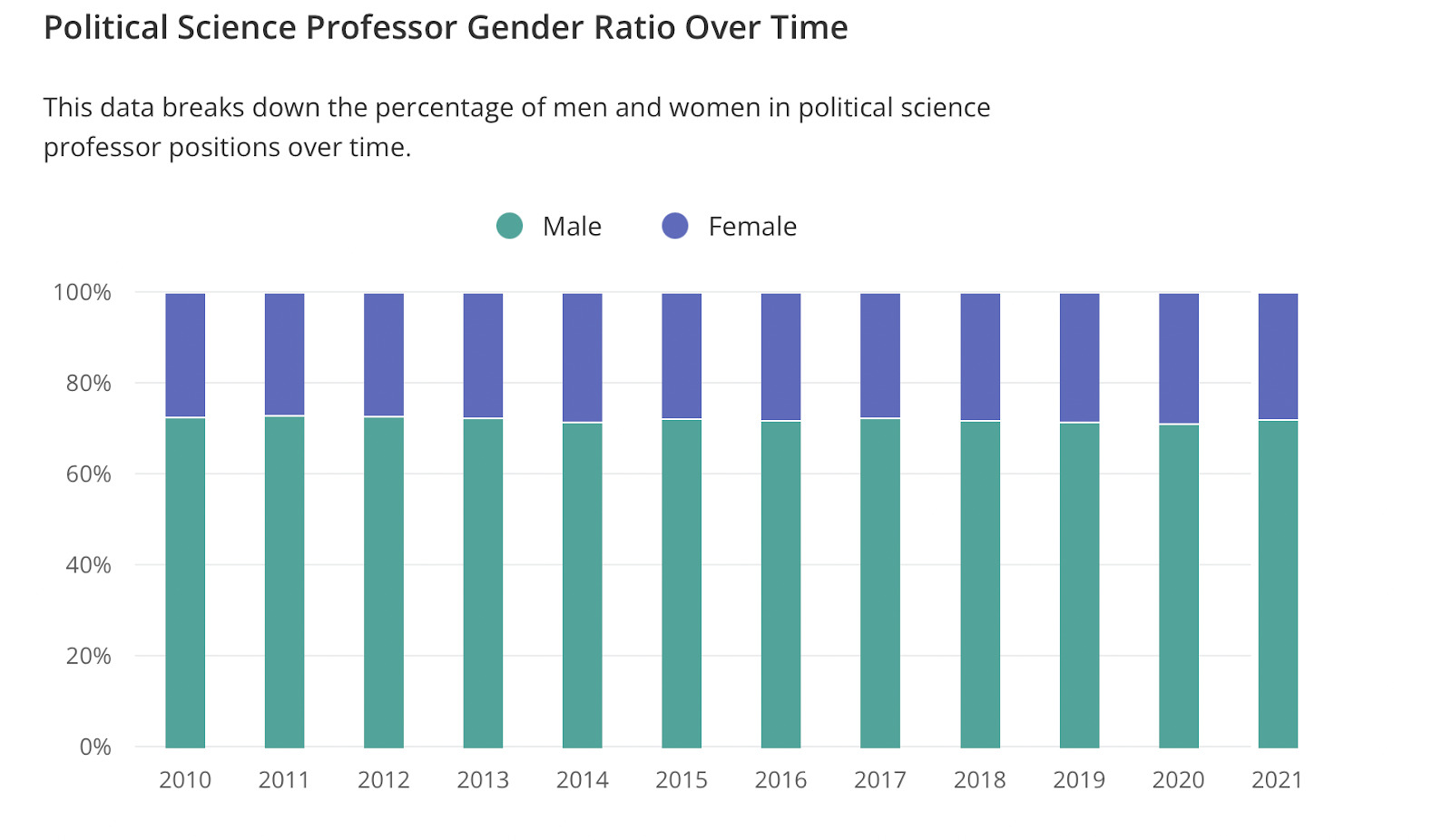

Examining the discrepancies in gender representation in political science departments, I found that across all universities and colleges in the United States an average 27.6% of political science professors are women and 72.4% of political science professors are men (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). This ratio has remained almost stagnant over the past 10 years (Figure 1). On the opposite end of the student-professor power relationship, more women are attending universities, and, subsequently, more women are majoring in political science. Fifty years ago, enrollment in universities was 60% male and 40% female, but now the reverse is true (West, 2021). Additionally, from 1971 to 2020, the percentage of women graduates with a political science bachelor’s degree increased from 36.8% to 51.7% (Perry, 2022). In comparison to professions like Biology, Architecture, and Physical Sciences, this increase is small, but an increase nonetheless (Perry, 2022). This increase can be attributed to an overall rise in the representation of women in universities, political science professions, and political science faculty.

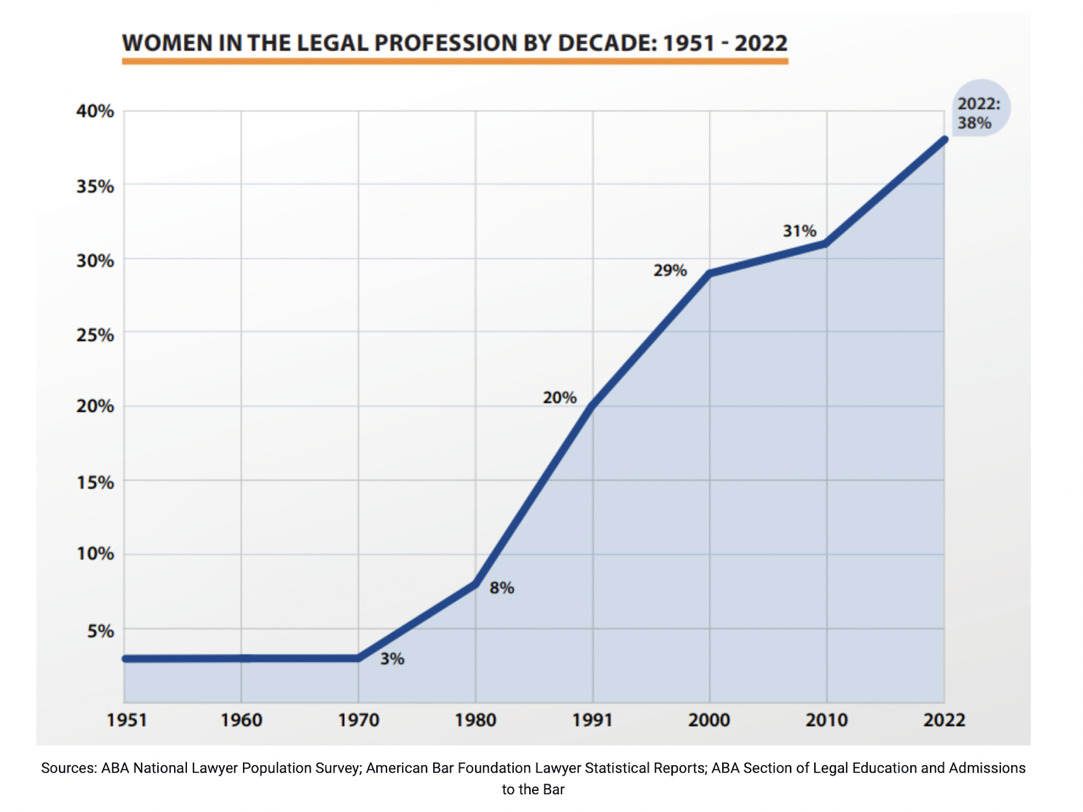

With women closing the gender gap as students, but not as professors, it is important to look at the gender makeup of professional political science majors to determine if the underrepresentation of female professors affects students’ career trajectories. To do so, I reviewed the top three career paths political science students take, law, government, and business. Women now also consistently outnumber men in law school each year; however, in 2022, only 38.3% of lawyers were female while 61.5% were male (Bagby, 2022; Figure 2). Women also surpassed men in law school graduation rate for the first time in 2017, with 50.3% of graduates identifying as a woman (Rowe, 2018). But, again, despite women outnumbering men in the prerequisites of this profession, they are still underrepresented in this area of the workforce. The second most common career path for political science graduates is government-related positions, which have a similar gender makeup to law. Women make up close to 25% of the total elected officials at the local, state, and national levels (Represent Women, 2022). Globally, women make up 50% or more of local-level government officials in only three countries (UN Women, 2023).

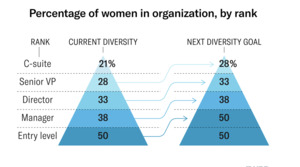

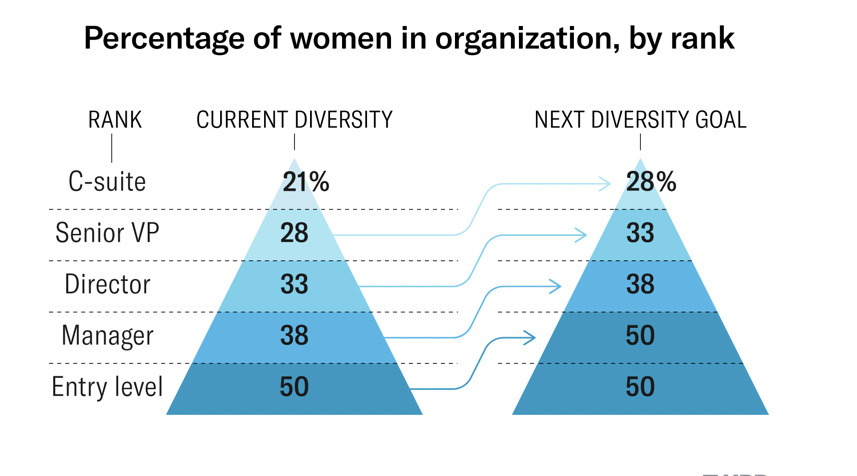

Women are also less likely to work in business – the third primary destination for undergraduate political science majors – than men. Women make up about half of entry-level employees; however, this dramatically drops at the next level; women only make up 38% of managers in the U.S. (Chilazi et al., 2021; Figure 3). With an already extremely low percentage of women leaders in business, that number is further decreased as they leave their roles at much higher rates than men and more rapidly than ever seen before (Huang et al., 2022). Due to these difficulties in breaking into the current business industry, women are starting their businesses at higher rates than men, and this has greatly improved female representation; yet, the industry still remains male-dominated (Lesonsky, 2023). Overall, the male-to-female ratio of students in political science education is nearly equal, while the male-to-female ratio of political science professors and those employed in the top three subsequent political science careers, law, government, and business, leans overwhelmingly toward men.

Discussion

The above statistics are a result of the severe underrepresentation of women in political science professorships and a misogynistic environment. Despite women making up larger and larger percentages of university students and political science students, they are still disproportionately represented on the faculty side, leading to a heavily male-dominated environment. Reexamining the power relationship between students and professors, we know that the professor’s influence can be profound. Additionally, taking into account symbolic interactionism, an educator’s implicit bias will be present in the classroom and projected through repeated action toward students through the use of gender-specific language, projecting in-class preferences, or opportunity limitations based on gender. Symbolic interactionism and uneven student-professor power relationships ensure that the exchange of bias or simply the transfer of biased ideals will inevitably reach students, from their professors. Since these professors, who could influence their students, are mainly men, it is almost certain that gender bias exists within them and if not explicitly in the classroom, implicitly in grading, opportunities given, general views of students, and more.

Researchers and authors, Becky Francis, and Christine Skelton, studied how male professors have the challenge of being in a profession that is widely considered to be feminine (teaching), and this often implicitly encourages them to hold onto their masculine traits as much as possible and exert them in the classroom (Francis & Skelton, 2001). Male educators will often take advantage of their power in the classroom, creating inappropriate, uncomfortable, and misogynistic environments. This is done through making comments on female students’ bodies, on male students’ masculinity traits, stressing certain parts of the curriculum while diminishing others, and more, all to exert their masculinity. The need to demonstrate their masculinity comes from being employed in a profession associated with femininity. Student-professor power relationships can also lead the student to strive for the approval or recognition of the professor, discouraging many students from challenging the professors’ ways of teaching or how they run their classroom out of fear of being alienated. Each student experiences this differently; while some female students feel gratified by receiving treatment viewed more specifically to common gender roles as it reaffirms their femininity, others may find this behavior inappropriate or abusive. Either way, it does affect female students. Francis and Skelton recognized that mental health, perceptions of the teacher, the class, herself, and her career are all female student ideals that have the potential to be heavily influenced by symbolic interactionism from male professors in their self-created misogynistic environments (2001).

Conclusion

With the combination of the data I pulled, Francis and Skelton’s findings, and earlier referenced literature reviews, I can establish a correlation in the relationship between gender representation in U.S. political science university departments and female students’ career trajectories. The data proves that women are underrepresented in the power positions of these departments while making up the largest percentage of the potentially vulnerable population. This already puts them in a position to be subjected to the actions and biases of those in power. Through the literature review, I was able to identify how bias can be displayed differently, in implicit or explicit forms, and how it can be transferred to students through symbolic interactionism. I also reviewed the possibility of this bias being gender-based, especially if those who could be projecting it are of the opposite gender of the group we are focusing on, which in this case is women. Finally, I examined the career trajectories of political science majors. Women make up half of political science graduates, but in the top three career paths for political science majors (law, government, and business), they are in the minority.

This research is not intended to blame a specific group; rather, it is an attempt to identify the connection between professors holding innate bias and thus impacting their students’ careers with the subsequent problem of women being underrepresented in political science. This research and the conclusions made are also solely based on already existing data; therefore, I acknowledge the limitations of knowing the true wide-scale applicability of it. However, I would like to highlight that this specific relationship, which I have deemed to be a correlation, would benefit from further research to explore real-world impacts. With the establishment of a correlation relationship between misrepresentation in political science departments and then in political science careers, education is identified as one of the roots of the problem. This can be extremely useful in being applied to larger issues such as gender inequality, discrimination, sexism, and more, to also identify the roots of those problems. By doing this, solutions for these topics can take a more effective form if they take into consideration what my conclusion is suggesting. Simply put, I have concluded that the original issue of women being misrepresented in university science political department staff affects the trajectory of political science female students’ careers. The uneven gender representation can cause women to be diverted from careers in political science.