INTRODUCTION

Structural violence denotes any form of injustice that may be embedded in institutional and social structures in society that result in harm to an individuals’ well-being (Farmer, 2004; Galtung, 1969). Involuntary hospitalization similar to a “war in our city streets” seeks to impose measures of social control and appropriate the right to choice and human dignity. In November of 2022, New York City Mayor Eric Adams expanded the use of involuntary transportation and hospitalization, lowered the threshold to determine harm and provided a directive to authorities to remove individuals from the streets and subways who appear unable to meet basic needs. Critics argue that involuntary hospitalization is not necessarily compassionate care. (Linton, 2022) In regard to New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ policy of involuntary hospitalization of emotionally disturbed persons -critics warn that rather than helping the homeless and mentally ill realize recovery, Adams’ plan could further destabilize the very people it claims to help. Beth Haroules, a senior staff attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union warns the following:

“At the end of the day, I would want government actors, when exercising police power, to be very cognizant of the collateral consequences of being involuntarily committed and exposed to involuntary treatment,” Haroules said. “The collateral consequences are very extreme and traumatizing—and can in fact prevent a person from recovering and participating in society.”

In any given year, more than 1 in 5 New Yorkers has a symptom of mental illness and jail has become the first response to handle them. Studies have also found that people of color are more likely to be forced into treatment or hospitalization than whites—including in New York. There are more mentally ill patients in jail than in hospitals. (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SAMHSA.gov) The potential to prioritize force and exclusion over rehabilitation and long term care potentially exacerbates the crisis. We rest the livelihood of our most vulnerable populations – mentally ill, incarcerated, Other, on the moral judgment of first responders. How is the act of institutionalizing and involuntarily committing such patients a complicated question for peacebuilding and public health? In New York City, emergency medical services and consequently medical doctors are being asked to take the role of judge, jury, and executioner as decisions about admission, treatment and hospital stay are at their discretion. Making matters worse, the city’s mental health providers are already underfunded, understaffed, and struggle to care for the number of people currently being poured into the system.

The relationship between public health and peacebuilding- although intimately connected is often overlooked. A whole of society approach is required to handle these very complex debates. Social control may be the guise for “harm reduction” or the intent to minimize the impact of individuals who pose a potential threat to an existing social ecosystem and further build community resilience. War is also understood to have profound consequences for public health and safety. For example, existing public health access to healthcare can dramatically change outcomes for victims of war and violence. The standpoint of human rights doctrine for individuals in war torn nations or conflict ridden border zones has utility to analyze vulnerable individuals in our “peaceful” democracies. In the following qualitative study, the story of incarcerated emotionally disturbed patients from ambulatory shifts in a large urban city in the United States will be analyzed through observation to elucidate the greater debate that exists between structural violence, public health and involuntary hospitalization. A more balanced approach will require a compassionate solution and better moral decision making powers that restore dignity to the individual whether -homeless or incarcerated. Uncomfortable truths and multiple tensions clash in this very sensitive debate about the politics of “Otherness” and the case studies in this study present realities that complicate the dialogue related to the politics of public health, peacebuilding and human rights. Historical, sociological and ethical perspectives will be analyzed to provide frameworks for this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Historical perspectives

Dating back to the 1870’s the primary sites for mental health care in America were coined “mental hospitals and lunatic asylums”. Such hospitals essentially became warehouses for the most marginalized and vulnerable in society. Most often, immigrants, ethnic minorities and those of the working class would become admitted. The 1960’s experienced a movement to advocate for home and community care for psychiatric patients and sought changes to policy and societal attitudes. The changes to law in the 1970’s were beneficial to patients with insurance and supportive families. It left uninsured individuals, who are disproportionately poor and of minority background - to cycle in and out of prisons as jails became ad hoc “mental health care providers”. In 1999, Kendra’s Law took effect concerning involuntary outpatient commitment where courts were given authority to order certain individuals undergo psychiatric treatment. Mayor Eric Adams has greatly expanded this law and has granted the authority to involuntarily remove people to law enforcement and first responders. Fainman-Adelman (2020) shares arguments for the challenges that exist for safety.

“First responders (including police) are reluctantly taking over the role many believe that should involve psychiatrists or other mental health professionals. The justice system in turn is tasked with solving the social problems that occur as a consequence of a severe mental illness. The alternative to incarceration is involuntary hospitalization. The misconception held by some mental health and legal professionals is that involuntary hospitalization can be the best thing for people with severe mental illness; and protects those with severe mental illnesses from ending up in the justice system. However, there is inconclusive evidence of the effectiveness of involuntary hospitalization. Ironically, one of the reasons why there is an overrepresentation of persons with serious mental illness in the justice system is because of deinstitutionalization. Following the arrival of antipsychotics in the 1950s, the public view became that it was not necessary to detain individuals with mental illness since treatment psychiatric symptoms was available. By the 1990s the number of psychiatric inpatients had been reduced from 550,000 in 1950 to 30,000. Nonetheless, the issue became that individuals with serious mental illness, who were disproportionately homeless or extremely low-income, could not afford access to these new treatments. As a result, the number of individuals with untreated serious mental illness within the prison population increased.”

Sociological perspectives

Sociological frameworks and discourses of Otherness also lend frameworks for this larger debate. Who belongs in our vision of peaceful civil society? This question becomes a double edged sword for numerous reasons- but of most significance is the response to “Otherness”. Benhabib’s (2004) argues that the tensions with “Otherness” is a barrier to nation-states in their abilities to establish codes of belonging, and to negotiate secure boundaries and borders and to establish who belongs. Multiple tensions are at play – the politics of Otherness, morality and the ethics of care as well as the tension to realize a peaceful society. On the other hand, the imagined moral code of right and wrong is a blurred landscape and achieving “peace” in the world is correlated with engaging violence. To preserve “global peace”, violence is employed in the guise of democracy. To realize “peace in the streets”, mass unnecessary incarcerations take place. To preserve “morality and peace”, groups of people are admonished with homophobia. To foster “peaceful schools” for children, segregation takes place to ensure one’s children do not attend schools with the perceived dangerous “Other”. The knowledge within us about the social order is symbolically violent and reproduced with little interruption. Such troubled knowledge and normalized ideas about violent “peace” when confronted do not necessarily become de- stabilized. Confrontations do not necessarily lead to transformation in many instances because humans themselves possess a gaze that is deeply embedded in privilege. The gaze of “Otherness” in moments of crises are closely tied to moral decision making for first responders. The level of trust or mistrust in a moment of crises is where excessive force or inhumane acts can take place.

Panayota Gounari (2013) reminds us that, “subjective violence always stands in need of spectators since it is through their gaze that it takes on meaning and importance, and it is the spectators’ interpretations that make it what it is” (p. 71). Acting to resolve subjective violence, however, requires us to merely see a segment of a larger problem and oftentimes such activism simply aims to solve the symptom that is the root of larger systemic problems. Coupled with this, Gounari also argues that “there is a shift from the collective to the personal, from social issues to individual problems. Concerns for personal safety overwrite concerns of participation in the public sphere”. Further going on to state, “Maybe that explains in part why often people so alienated in capitalist societies remain idle in the face of the violation of other people’s safety, until their own safety is at stake” (p. 73). This is a powerful argument and serves to remind us about the difficult work we face. Panayota Gounari challenges peace educators to begin with defining what peace is not and to engage in critical engagement with civil life and thus allow one to take ownership of post- memory in order to begin raising questions about agency and subjectivity. In order to realize transformation, the intention and desire needs to exist amongst civil participants. When does it become important for everyday civilians to notice the violence both symbolic and overt in our communities? Without such intention or desire we miss variables in the equation and return to superficial tolerance paradigms and accept the world as is and have little or no impact. To seek knowledge and burden oneself about the many forms of structural violence in the world, we must be willing to engage and give relevance to these issues. An alternative socio-political and cultural consciousness should ideally be cultivated as public servants can be transformed from ordinary “spectators” to agents of political action.

Frameworks can be imagined where human dignity is measured by a lens of “Otherness” in the emergency public health system. Macqueen’s (2000) research on peace building through health initiatives describes a “health-peace initiative” as those that intend to simultaneously improve peace, security and health of a population. Five peace building mechanisms, conflict management, solidarity, strengthening the social fabric, dissent and restricting the destructiveness of war. These mechanisms were described as being built through three characteristics of healthcare: altruism or the human “impulse to care”, science or accurate and “unbiased” information about policies, and legitimacy or the imagined discourse and culture of health professionals as highly regarded and honest. Although it is argued that the process is complex and difficult, the most interesting argument made by Macqueen (2000) is that healthcare is one of the chief means by which members of a society express their commitment to one another’s well-being. Ethics and moral decision making also play a key role in how an individual actor may respond in a moment of crisis. The outcome for a patient is highly dependent on the moral judgment and ethical behavior of the actor who approaches them.

Ethical Perspectives

Throughout the course of history, the topic of ethics has been a staple of philosophical thought. This dates back to Greek thinkers such as Socrates who examined the moral beliefs of others using his infamous Socratic method. Plato continued Socrates’ examination of ethics by developing one of the first observed moral dilemmas in observed human history, the Euthyphro Dilemma. The Euthyphro Dilemma examines the nature of piety (a cornerstone of Greek ethics); they ask if a pious man is loved by the gods due to his piety or if he is pious as a result of his love towards the gods. As human history developed so did the questions surrounding ethics - spearheaded by famous philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Nietzsche. It was not until the 20th century however, when the study of ethics and moral development was explored in concrete studies. Lawrence Kohlberg, inspired by Jean Piaget, wrote his dissertation on differing stages of moral development. Kohlberg dedicated his research to these stages and is now a pivotal figure regarding moral development and ethics. Kohlberg outlined levels of moral development, mainly pre-conventional, conventional and post conventional. He used hypothetical dilemmas to study moral development of 10-16 year old American males. The key gap in his work was the absence of women in his study- and which was recognized and challenged by Carol Gilligan (1982) who shattered the notion of male centered psychological research, resulting in the Gilligan Kohlberg debate. Gender disparities exist in moral growth and Gilligan argues that Kohlberg’s stages are not universal. The central question in this debate was whether men and women defined morality differently. Since Gilligan’s claim, research studies have shown that both females are at par or at a higher level of development when processing hypothetical dilemmas. (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000; W. Walker, 2005) Other studies have denied any gender differences in moral development.(Caravita et al., 2012; Gibbs et al., 1984; L. J. Walker & Hennig, 1999) The universality of Kohlberg’s theory remains a great debate and the importance of scientific basis of moral development should be considered.

Several studies elucidate some interesting findings in regard to the question of morality and development in relation to gender and identity differences. Lawrence Walker (2005) conducted a comprehensive review of the literature and found the following patterns in regard to gender and morality (a) that gender explains a negligible amount of the variability in moral reasoning development, (b) that abundant empirical evidence indicates no support for the idea that Kohlberg’s model down scores the reasoning of women and those with a care orientation, and (c) that Gilligan’s claim of gender polarity in moral orientations cannot be substantiated in light of small effect sizes in analyses of gender differences. Therefore the debate remains for gender differences in moral development. For example, Khan and Stagnaro (2016) researched the influence of multiple group identities on moral foundations. The findings are relevant and provide additional frameworks to understand moral development. The Moral Foundations Theory and Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) were utilized to examine moral response. The findings of the study were compelling and found that ethnic identity influenced Indian male response to moral foundations at the highest rate(Khan 1). In particular Hindu men had the strongest correlation between ethnic identity and moral foundation development. There was a noted difference with Hindu women. White women in the study also demonstrated a connection to gender-based experience as a factor influencing moral foundations(2). This was understood by the researchers to be due to male conceptualization of moral foundations as commitments to the ethnic group whereas women view them as tied to gender commitments. The question is complex with many variables to understand.

Religion has also been documented to stimulate certain areas in the brain during acts of moral reasoning. A study spearheaded by Julie F Christensen - a researcher in human cognition at the University of the Balearic Islands - analyzed how religion influenced responses to moral dilemmas and also monitored neural activity whilst they answered the questions. This exemplifies the notion that differing sociocultural variables and the upbringing that comes with it often impact one’s moral compass significantly. The most significant data stems from the differing types of responses recorded. Religious participants leaned towards responses that are predicated off following a set of rules is an exemplification of a key cornerstone of religious ethics - following set rules that dictate morality. According to a preliminary study (Singh 2023) on the impact of religion moral development 135 adolescents- responded and the trends are compelling. The trends inform us- of moral decision making attitudes of adolescents- and perhaps further the idea of what informs an individual in their decision making that will gravely impact others. For example. in New York City, police officers will conduct “mercy bookings” where someone will be arrested for a minor offense in the hopes they will have access to food and medical care in the jail. How one chooses to act in a moment of crises, their moral sense of obligation to care for others and further the decision to save a life lends to these very debates on ethical behavior.

Research Objectives

The debate on involuntary hospitalization is a topic that is relevant and controversial with a murky understanding of its short and long term impact. An understanding of what takes place during moments of forced commitment in the ambulance and at the scene have not been studied. The use of qualitative research and a participant observer lens will provide an intimate portrait of the challenges and obstacles that ensue as first responders and rescue teams are called to the scene. This knowledge can potentially provide informed viewpoints about moral decision making and human dignity, public health and controversial policies. Mayor Eric Adams’ new law has only been in effect for a few months and this study provides an understanding of the immediate impact of what is taking place in the field. There are few research studies that handle the human rights perspective of this issue and further there is a lack of studies that look in detail at the relationship between peace building and public health.

METHODOLOGY

Qualitative methods were used to gather data. In order to uncover or reconstruct people’s practices, performances, behaviors, and actions within a naturalistic setting, participant observation involves the researcher immersed in the day-to-day tacit aspects of their activities, rituals, and interactions (Dewalt & Dewalt, 2010; Kawulich, 2005; 2003 (Mulhall) According to Bailliard, Aldrich, & Dickie (2013), participant observation is referred to as the “heart of ethnographic fieldwork” because it gives researchers the chance to interact with participants in real-world situations that are typical of everyday life. Dewalt & Dewalt, 2010). (1) We can learn from observation, (2) being actively involved in the lives of people brings the ethnographer closer to understanding the participants’ point of view, and (3) achieving understanding of people and their behaviors is possible are the three guiding assumptions of participant observation (Dewalt & Dewalt, 2010).

In the late 19th century, participant observation emerged as an ethnographic field method for the study of small, homogenous cultures, with its roots in anthropology (Dahlke et al., 2015). Positive epistemology, in which researchers sought to immerse themselves in the life of “the other” in order to accurately record and represent a culture, was prevalent in early ethnographies. However, constructivist, interpretivist, and critical paradigmatic perspectives are now included in contemporary ethnographic studies (Huot & Laliberte Rudman, 2015). Member perception isn’t about precisely addressing a specific culture, yet rather consideration is moved toward noticing the person inside their normal setting to grasp them from a constructivist, interpretivist, or basic paradigmatic lens.

The use of exploratory case studies will serve to explore situations from an intimate perspective and provide the ability to explore phenomenon from a variety of lenses Yin (2013). Although case studies allow for unpredictability-the unique perspectives that can be analyzed provide key insight. According to Harland (2014) the use of case studies allows one to understand complex social situations that need to be experienced yourself or from the experiences of others.

DATA/CASE STUDIES

I share the following case studies from the intimate perspective of a first responder and human rights activist. Data collected was observational and hence no harm or direct interaction took place with the population under study. Prisoners are regarded as vulnerable persons and data in this paper was observational, posed minimal risk and their identities remained anonymous. The prisoners’ identities are not revealed and their real names not used. In this study, data was collected from the 5 males and 5 females in the ambulatory crew. All crew members will also remain anonymous in data analysis and findings. Interviews and responses from the workers were analyzed to understand their perceptions of the experience of forced hospitalization. The role of an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) is to provide basic life support to a patient in need. Through rigorous training, an EMT understands when and how to enter a situation, the basics of stabilizing a patient and further transporting their care to an emergency room at a hospital. On the heels of a newly passed law of involuntary hospitalization – our team was led to maximum security prisons to treat the incarcerated. Only law enforcement can restrain a patient and therefore requires their presence in all fronts. From an ethical standpoint, there was no question or doubt about our responsibilities as a team to assist in the care of the patients. From a moral and human standpoint, however, the following case studies illuminate some of the realities and challenges that arose in the process- workplace violence for EMS workers, cycles of mistrust between incarcerated and law enforcement that may lead to poor outcomes for care and their social-emotional response toward the situation.

Case Study #1 Ronald Refuses

The police officer held their hand on the holster- gun in place ready to be drawn. The patient in their inmate jumpsuit, handcuffed to the gurney ambulance continued to shout expletives and bang their head and legs in all directions. The patient, appearing to be refusing to be taken to the hospital – was being involuntarily hospitalized and seemed to pose a clear danger to themselves and the emergency medical staff. The ambulance roared through the busy city streets and arrived at the emergency room as the chaos continued as there were no beds available today. The dispatch to the first responders read: male, suicidal, violent. Walking down the halls of the maximum security prison, police escorts led us to a jail cell with the prisoner named Ronald (anonymous name). Ronald was standing up with his fists raised- visibly angry and defiant. His offense was armed robbery and assault. As he watched us enter near his cell- he spat and shouted derogatory expletives. Ronald had been in solitary confinement. None of us clearly understood the circumstances around the patient. It was at the discretion of the prison guards to determine that hospitalization was needed. The officers proceeded to enter the cell-with tasers and guns ready to be drawn. One officer was kicked in the leg by the patient. Ronald received a sedative so he could be safely transported. We waited as it began to take effect. It was clear that Ronald was resisting in every way- yet it was a decision made by the prison officers that he needed to be admitted and taken to the hospital. We were told Ronald was suicidal and was in danger of self- harm. It was important for all members on the scene to be protected -the prisoner included. Armed officers were required for the duration of the ambulance ride. Ronald was ultimately taken to the ER and continued to act out and threaten violence to medical staff there. It was uncertain what level of treatment would ensue and it was obvious that he would later return to his jail cell. Comments from the EMS workers in the ambulance were recorded and demonstrated a pattern of fear:

“Wow that was close, I was a bit nervous when the patient became agitated. I did not know who to proceed to protect myself” (Female EMS worker)

“I guess I need to train more and get in athletic shape to handle that violent patient.” (Male, EMS worker)

“I always wonder if I will be attacked-it makes me wonder why I do this.” (Female, EMS worker)

Emergency medical service (EMS) responders are committed to delivering patient care in highly variable scenarios that are high- stress and high-risk. Violence is one unpredictable variable that can face EMS workers. According to research,

“prehospital emergency care workers stand out because of the nature of their work environment which is uncontrolled and often involves acute situations. They have a patient population that is more heterogeneous than a mental health ward or aged care facility. Workers are less likely to have a previous relationship with the patient, unlike a family physician or a dialysis nurse. Additionally, patients and associates present to emergency care with already elevated stress levels” (Spelten et al., 2020)

The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes workplace violence into physical and psychological violence, which includes verbal violence. According to data, between 60-90% of EMS workers face physical or verbal abuse. EMS workers are a valuable and crucial health safety net for the public and workers often place the safety of the patient ahead of their own safety.

According to Murray and Davis et al (2019)

In studies measuring career prevalence, between 57 and 93 percent of EMS responders reported having experienced at least one act of verbal and/or physical violence during their career.21,24,26,27,46–48 A 2013 LEADS found that among the 1789 respondents of nationally registered EMTs in the United States, 69 percent experienced at least one form of physical and/or verbal violence in the last twelve months.44 Furthermore, 44 percent experienced one or more forms of physical violence over the same study period.44 Gormley et al.44 defined violence in seven categories: cursing or making threats; punching, slapping, or scratching; spitting; biting; being struck with an object; stabbing or stabbing attempt; and shooting or shooting attempt. A New England study with a convenience sample of EMTs found the prevalence rate of violence to be 20.3/100 full-time employees/year. Thirty-eight percent of those surveyed reported multiple assaults within the last six months, and one EMT reported being assaulted nine times during that same six-month period.

It is interesting to note that EMS responders rarely report or document violence in the workplace. Yet the scene in the ambulance with Ronald was riddled with unpredictable situations-armed officers, untrained EMS workers and a restrained violent patient- and could easily have turned volatile and potentially fatal. Intervention policies and frameworks need to be developed as well as identification of risk factors. Results of a study (Spelten, van Vuuren et al. 2022) that analyzed how EMS workers respond to violence provided mixed results. Participants expressed some desire for self- defense and de-escalation training- although many felt they had developed their own strategies to address perpetrators. Other themes that were discussed in the study were support 1) for refusing patient health care to avoid volatile situations 2) prevention strategies and public campaigns to prevent violence 3) communication between organizations/flagging patients 4) dispatch providing crucial information. The broad conclusions of the study point to workers needing to rely on a wider systems based support and moving away from workers using personalized generic de-escalation techniques. Moral distress plays a role in the ability of healthcare professionals to conduct their work. Moral distress, a term coined by Andrew Jameton (1984), is characterized by a phenomenon where a clinician understands the correct course of action for their patient yet are unable to perform such action. Competing responsibilities to uphold professional ethics, meeting organizational requirements and the pressures from policy makers may impede the ability of the worker to fulfill the action for the patient (Moffat, 2014). The violent aspect of these cases should be a reason to pause and evaluate the manner involuntary hospitalizations can potentially do more harm than good.

Case Study #2 Marilyn and self-harm

The case of Marilyn (anonymous name) illuminates the cycle of distrust in care that can pose a challenge to public health. Marilyn appeared to be a middle aged inmate who takes weekly visits to the ER due to her intense self-harm in her prison cell. When we arrived at her cell she was sitting on a chair, chained with her head cocked to one side. We were told that she had been banging her head repeatedly on the wall in order to become unconscious. It was our role to then take her to the emergency room, with armed guards in tow. A few officers were deflated and understood Marilyn’s pattern. The general understanding was that her self- harm was intentional in order to take a break from the prison cell. Comments were noted from staff that elucidated a level of distrust in the intentions of the patient.

“She does this every day to get out of the jail.” (Male officer)

“I will need to assist in the ambulance even though she appears unconscious- she has done this before.” (Female officer)

“I am sure you will be back here soon again as we are pretty sure she will do this again.” (Male officer)

Trust plays a key role in determining timing of intervention for incarcerated patients. With repeated incidents of self- harm- it can become challenging to discern between manipulative behavior and further builds distrust within prisons.

According to research, Dear and colleagues (2000), explain that “researchers have noted a desire among prison staff to distinguish between genuine suicide attempts and manipulative acts of self-harm in which the goal is to gain attention or force a change in one’s circumstances” (p. 160). In addition, researchers state that

“prison staff appears to operate a distinction between genuine and ‘non-genuine’ forms of self-harm, with the latter being perceived – and strongly resented – as manipulative and exploitative” (Marzano, et al., 2012, p. 2). Some correctional staff perceive inmates who engage in repeated superficial self-harm or convey they are feeling suicidal as manipulative and calculating for a desired outcome (Cummings & Thompson, 2009).

Short and colleagues (2009) note that, the amount of time [correctional officers] spend with prisoners means they may be the only staff able to notice a change in any individual’s behavior, and are likely to know about new crisis situations that the prisoner might be experiencing, which may be antecedents to an act of self-harm. (p. 409) Correctional officers can therefore play important roles not only in recognizing inmates who are at risk of engaging in DSH, but also in providing valuable insight related to the best treatment and management responses when inmates engage in DSH (Kenning et al., 2010; Short et al., 2009) The third case elucidates how involuntary hospitalization can be one potentially life-saving act.

Case Study #3 Sylvester is dead

The code for cardiac arrest popped up on the dispatch. Within a second, the ambulance veered through streets at top speed to arrive at the prison. Running at top speed through the street and entering the prison- we were confronted with a body laying listless, shirtless with no pulse. The patient appeared to be unresponsive. Paramedics, EMT, police officers as well as firefighters were all crammed into the prison cell as Sylvester (anonymous name) may have been pronounced dead. A web of tubes, medicines and machines were attached to his body. CPR ensued and all hands were working with their utmost effort to revive him. 1,2,3,4,5 I gave chest compressions. In that moment- the only thought that went through my mind was to garner all my strength to save his life. The moral decision was to save his life regardless of all circumstances. Health as a human right -Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights- was upheld and honored. The seconds seemed endless and then suddenly a pulse was revived. It was quite easily one of the most triumphant moments of my life. We saved a life. This experience complicates the debate about involuntary hospitalization because there are moments where the policy may save a life. The debate is complicated. Fellow EMS workers made the following comments about this moment.

“This is what we train for- saving lives and it is worth it.” (Female EMS worker)

“We have to make sure he has his live cuffs on- he is alive and kicking we brought him back.” (Male EMS worker)

"This is his second life- he was gone- and look at this! (Male EMS worker)

Within the cycles of violence and mistrust- lives can be saved. When Sylvester was revived- handcuffs were again placed on his arms and legs and an armed officer joined us in the ambulance to admit him to the emergency room. The emotional response of the EMS workers is important to understand as it sheds light on the dilemmas that arise in each moment during a rescue.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

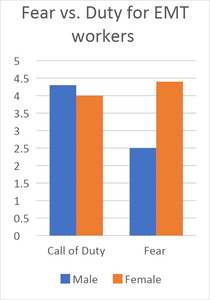

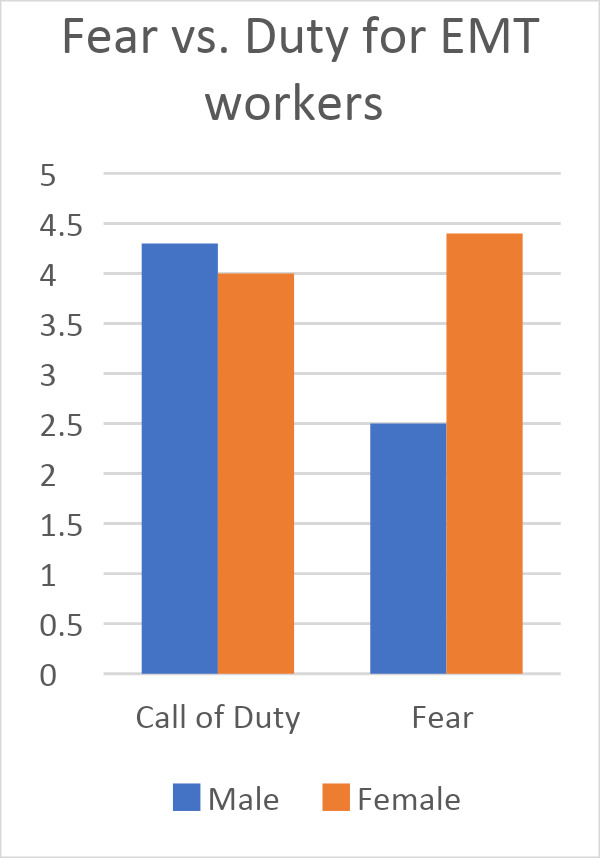

The responses of the 10 ambulatory crew members revealed a tension between the call of duty and fear for their safety as an emotional response during their ambulatory shifts. 0-5 was the rating with 5 being the strongest value. The below chart reveals a stronger emotion of fear for female EMT workers and a comparable level for both male and female EMT workers for call of duty.

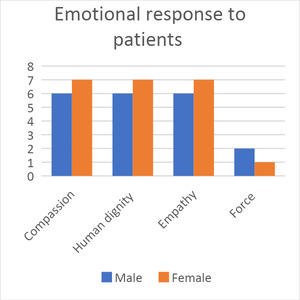

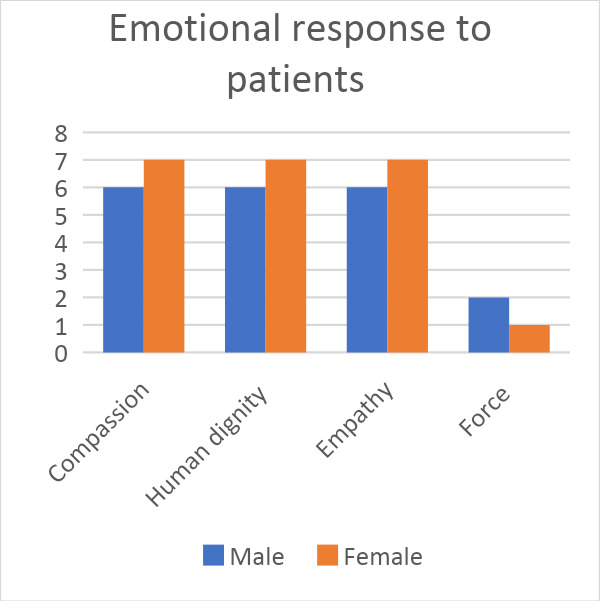

The findings also reveal a sense of empathy for patients and feelings of frustration about the well-being treatment protocol. 0-8 was the rating with 8 being the strongest value. When the EMS workers were asked about what was most important for them as they treated patients in situations of incarceration- the overwhelming data reveals a strong correlation with compassion, human dignity and empathy for the patient. Force was the weakest variable for both male and female workers. These preliminary findings of the short impact of forced hospitalization elucidate the controversial nature of the policy. It also reveals the human side of these cases and the complexities of public health.

IMPLICATIONS

It can be argued that sacrificing human rights under the rubric of security or “public peace” is almost always unnecessary and counterproductive in a free society. As Benjamin Franklin said, “[t]hose who would give up an essential liberty to purchase temporary security deserve neither liberty nor security.” Public health and peace are intimately connected and require a renewed focus. Civil libertarians, on the one hand, believe except under extreme circumstances- no person should be deprived of their liberty. On the other hand, most psychiatrists will understand a clinical situation and prescribe what they believe to be clinically necessary. This is certainly true for emergency psychiatrists and doctors as they are confronted with an out-of-control psychotic patient in the emergency room. Although a person with a mental illness who is suspected of committing a serious crime will most certainly be arrested and transported to jail, additional factors may explain why a severely mentally ill person suspected of committing a minor offense is incarcerated rather than transported to a hospital. A person who appears mentally ill to a mental health professional may not appear so to police officers who have not had sufficient training in recognizing and dealing with mentally ill persons. Mental illness may appear to the police as simply an arrest for alcohol or drug intoxication if a mentally ill individual has been abusing drugs at the time of arrest. The lines of communication need to be developed and training must certainly take place at all points of the process. This debate is complicated. There is a need to develop a different paradigm for public health- one where trust, partnership and human dignity are central. Mere incarceration and involuntary hospitalization may seem to be a fast solution- but the solution is quickly becoming a “train wreck” where systems are colliding and failing. Systemic issues to homelessness, poverty, drug addiction and mental illness need careful analysis and solutions based on compassion.

It becomes difficult to realize “peaceful” democracies that are based on structural violence of distrust, force and draconian measures for social control by way of involuntary hospitalization. First responders can restore dignity and rights to the patient – whether homeless or incarcerated. The original Hippocratic oath was a pledge to the gods to practice medicine and the consequent phrase primum non nocere - or do no harm is used as the oath for those in the medical profession. Healthcare professionals face the added dilemma of their oath to care for all persons and uphold their rights. Medical training is based on an oath of care- and we chip away at that very oath when the individuals in the ambulance- the violent patient, the armed police force, and the volunteer medic fear for their lives. This is a human rights crisis and a threat to global peace and security. In this study it was also revealed that EMS workers have a strong sense of duty and compassion towards their patients. We oftentimes focus our analyses on war zones, and global issues yet we overlook the everyday mundane levels of everyday structural violence that occur in our “peaceful” democracies- that cumulatively add to the overall threat to human dignity. On paper, we hail Article 25.1 or the human right to healthcare and we look no further. Yet everyday countless threats to human rights and peace occur the moment the wail of siren interrupts our quiet moment. The phenomenon known as Penrose’s Law, named after Lionel Penrose (1889-1972) and based on a study of European jails, noted that the number of prisons was inversely related to the number of individuals in “mental institutions”. This further begs the question to think about alternative solutions and care for the mentally ill. Non-profit intensive mobile treatment groups in New York City have found a degree of success where a gentler, more holistic approach is taken to mentally ill individuals. Taking food, medicine and treatment to where the individuals are rather than using force has been a more humane approach. An inclusive and compassionate public healthcare system can be the great enabler of the process of peacebuilding. If we as participants in the public sphere can imagine ourselves as not mere spectators but rather social agents of change and advocacy- perhaps there may be different outcomes.. As spectators in civil society- we assume the wail of the ambulance signifies- the saving of a life and the rush to preserve it- we rarely imagine – it to be the opposite of an uncertain fate.