INTRODUCTION

India’s institutional framework, rooted in democracy, draws upon a range of ideologies that were carefully debated during the drafting of the Constitution. This framework allows Indian democracy to unite the many diverse elements it encompasses. Yet, in practice, democratic institutions in India have struggled to protect themselves from pressures that critics describe as contributing to the “slow death” of democracy (Gupta & Jain, 2019).At the heart of this concern lies a politics of shifting priorities, increasingly shaped and distorted by sophisticated propaganda.

There have been many interpretations as to what constitutes sophisticated propaganda, and this analysis clarifies its meaning. The paper focuses on how the negative dimensions of propaganda have increasingly overshadowed its potential positive uses. By distinguishing between the two, and through reference to different theoretical perspectives, it becomes possible to outline how negative propaganda shapes contemporary politics in India. The discussion makes it clear that propaganda-driven politics has steadily gained strength, emerging from the Congress era, adapting through the multiparty system, and now centering around the BJP’s leadership.

Propaganda tools seek to shape public behavior in the service of vested interests. Such manipulation functions through media and journalism networks, extending a form of “perspective rationality” to audiences while serving political ends. Building on this understanding, the discussion turns to a modular analysis of the Indian political system and its interaction with other state institutions. This institutional review traces shifts from the historical political framework to the present power structure. Within this context, the essay pays particular attention to the media—both print and digital—where the intersection of journalism and propaganda becomes especially visible. The analysis highlights the ways in which mainstream media, social media, and digital platforms act as mediators, employing various propaganda techniques to reinforce the nexus between politics and journalism.

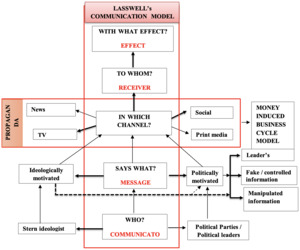

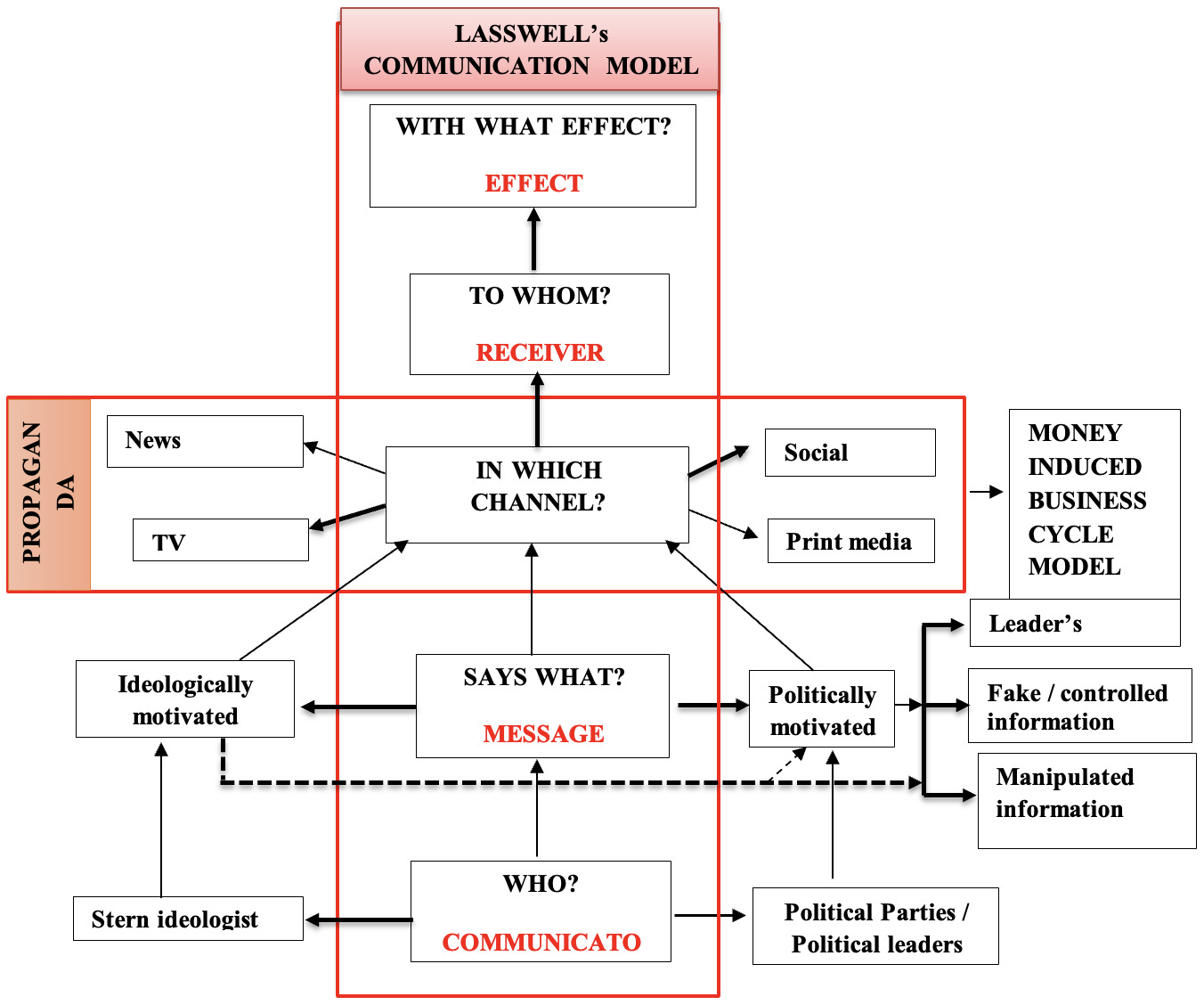

The discussion introduces an Indian Propaganda Model that can be understood in relation to the economic system, where the flow of money and the dynamics of credit shape the business economy. Within this framework, propaganda is sustained by industrial structures that echo Lasswell’s Communication Theory and reflect the filters of “Ownership” and “Advertising” identified in Chomsky and Herman’s Propaganda Model. Together, these elements highlight how economic power, media structures, and political messaging intersect to reinforce propaganda in an Indian cultural context.

Propaganda and Politics

In its most neutral sense, propaganda refers to the dissemination or promotion of particular ideas. The term can be traced back to 1621–1623, when it first appeared in Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (“Congregation for Propagating the Faith”), defined as “an organization, scheme, or movement for the propagation of a particular doctrine or practice”(Oxford English Dictionary, 2011). In this early usage, propaganda was closely associated with religious indoctrination(Fitzmaurice, 2018). Over time, however, both the form and meaning of propaganda have evolved, with scholars defining and analyzing it across multiple domains, whether historical, political, sociological, psychological, or interdisciplinary.

The evolving nature of propaganda has significantly altered its meaning, shifting it toward the instrumental spread of self-serving and often rigid ideologies. This negative connotation is commonly associated with the manipulation or concealment of factual information to advance specific interests. In contemporary usage, propaganda is widely understood as a form of mass persuasion; it is typically one-sided and emotionally charged and seeks to influence opinion by subverting rational judgment, whether through fear, omission, or deliberate deception. While definitions vary across disciplines, this study restricts the focus of propaganda to its political dimension and to the Indian Democratic system.

Propaganda Theory and Aim

The fundamental aim of propaganda is to reshape how people think about themselves and their society in ways that align with the propagandist’s motives. This transformation is pursued through communication strategies designed to mold public opinion. From a behavioral perspective, human actions can be considered responses to external stimuli, with behavior largely conditioned by the pursuit of rewards or the avoidance of punishment. Early communist theorists drew on this behaviorist approach to guide the mechanisms of propaganda, presenting information in ways that direct and redirect individual attention. Freudian theory offers another lens. Sigmund Freud’s model of the psyche, which divides the mind into the Id (pleasure-seeking), Ego (rational), and Superego (internalized social rules), helps explain why individuals yield to external demands. Freud argued that when the Superego dominates and suppresses the Id, individuals may become detached, uncritical, and submissive, behaving like “social automatons.” Propaganda theorists apply this framework to show how emotional and psychological vulnerabilities can be exploited to elicit specific reactions. Behaviorist and Freudian perspectives highlight how propaganda works by shaping individual states of mind and emotional responses. This psychological influence is central to propaganda politics and is exercised through the strategic use of propaganda techniques.

Propaganda in India: A Historical Analysis

The roots of the Indian political system can be traced to the pre-British era, and propaganda politics likewise has antecedents in the pre-imperial period. During the Early and Later Vedic periods, propaganda often took the form of persuasion closely tied to religious indoctrination. Political structures operated in close association with religious institutions, with custodians of faith seeking to advance their own beliefs and ideas. This intertwining of political authority and religious influence frequently gave rise to ideological conflicts and struggles (Mukherjee, 2023).

The discourse of propaganda politics in India shifted significantly under British rule. Colonial strategies of control and suppression introduced new dimensions to propaganda, rooted in materialistic and imperialistic tendencies. These techniques were reinforced through stern rhetoric and policy measures. Policies such as “Divide and Rule,” “Communalism,” “Westernisation,” and the so-called “Civilizing Mission” exemplify this approach. British propaganda was disseminated primarily through newspapers, radio, leaflets, and news sheets. One example was Hamara Hindustan, a four-page weekly printed in Urdu and first circulated in 1944 by the General Headquarters (GHQ) of India. It featured stories of the war in Europe and Asia, accompanied by maps and images, designed to cultivate loyalty and maintain support for the British cause.

At the same time, rival powers sought to influence Indian minds. Japanese propaganda targeted Indian troops through leaflets and radio broadcasts that urged them to join Japan in the struggle to “liberate” India. A “Free India” radio station was established in Saigon, calling on Indians to rise against British rule while Britain was weakened by war. Additional transmitters, including “Indian Independence” stations in Bangkok and Singapore and an “Indian Muslim Station,” further amplified this effort. Propaganda tools were then used to awaken the collective conscience of Indians, encouraging them to unite against a common adversary. Yet, following India’s independence, the dynamics of propaganda politics took on a markedly different form.

Propaganda Politics in Contemporary India

Before analyzing propaganda politics in India, it is essential to distinguish between the pre- and post-independence contexts. While the structural foundations of governance have remained relatively stable, the political fabric has undergone significant transformation, shaped by evolving public perceptions. During the pre-independence era, most members of society regarded the British as a common foreign adversary. In contrast, the post-independence period, built upon the foundations of institutional and ideological frameworks, has been marked by a diversity of interpretations and rationalities among citizens.

On this basis, the trajectory of propaganda politics in India has shifted dramatically, with multiple actors competing for influence within the political arena. These actors employ strategies that resonate with psychological theories of persuasion and behavior previously outlined. The political system itself has moved from Congress dominance to a multiparty framework and, in recent decades, has become increasingly centered around BJP-led politics. Consequently, contemporary analysis must focus on understanding the dynamics of propaganda within the current system of rulership.

Modi Government and Propaganda Narrative

A comparative study of propaganda politics in the Indian political system can be framed through the lens of behaviorist theory, which interprets individual reactions as responses to external stimuli. In the Indian context, such stimulus–response patterns are often shaped by the strategic use of propaganda tools. To illustrate this, the current ruling structure may be examined through the common techniques employed by propagandists.

One method is bandwagon propaganda, which operates on the principle of “follow-the-herd.” Here, propagandists persuade individuals to align with the dominant group. This tendency has played a central role in shaping persuasion strategies within Indian politics. Analysis of the Indian voting system demonstrates the prevalence of this effect. For instance, the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), drawing on data from the National Election Study 2014, confirmed the presence of a clear bandwagon effect in Indian elections (Neyazi, 2020). Political parties and leaders have increasingly recognized the importance of cultivating perceptions of a “wave” in their favor, a factor that helps explain the extravagant expenditures often associated with election campaigns in India. Notably, this form of propaganda is not confined to any single party but is widely utilized across the political spectrum (Neyazi, 2020)

A second technique is card stacking propaganda, in which selective facts are emphasized while others are omitted, thereby presenting a distorted picture to the public. This strategy has become a recurring feature of Indian political culture. Both ruling and opposition parties engage in such practices, often shifting their positions depending on whether they hold power or not. Opposition parties tend to adopt a stance of categorical resistance, which involves “opposing the ruling” at all costs. On the other hand, ruling parties often portray their ideologies in exclusively virtuous terms. As a result, the space for constructive criticism has diminished, giving rise to a phase of deadlock politics sustained by propaganda-based narratives. Examples of this dynamic include debates over the Rafale deal, disputes about back-series GDP estimates, controversies surrounding economic growth and unemployment data, and the delayed release of NSSO reports, all of which illustrate the selective use of information to shape public opinion (Rajgarhia, 2020).

There are also stances of glittering generality propaganda, in which propagandists rely on emotional or vague statements to persuade audiences. For example, the BJP government pledged to create 20 million jobs annually; however, unemployment in India remains a persistent concern, with the urban jobless rate reaching record highs. Such promises, often framed in terms of virtue words, align with populist rhetoric. Phrases like “fakir’s jholi” have frequently appeared in the speeches of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, appealing to cultural and emotional resonance rather than concrete policy detail.

The opposite technique, name-calling propaganda, relies on the deliberate use of pejorative labels to generate negative perceptions of an opposing group. A prominent example occurred during a rally in Wardha, where Prime Minister Modi asked, “How can the Congress be forgiven for insulting the Hindus in front of the world? Weren’t you hurt when you heard the word ‘Hindu terror’?” Such rhetoric represents the deployment of negative labeling to mobilize sentiment.

Beyond these direct appeals, the government engages in practices of information management, including controlling the timing of announcements, reframing controversial decisions (spinning), and emphasizing repeated but insubstantial messages that avoid engagement with underlying issues. Media controversies further illustrate these dynamics. For instance, journalist Arfa Khanum Sherwani’s speech at Aligarh Muslim University on the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was distorted in circulation. BJP spokesperson Amit Malviya claimed she advocated for the establishment of an Islamic state and urged protesters to feign solidarity with non-Muslims. In reality, her speech explicitly argued the opposite: she called on protesters to refrain from religious slogans and to preserve the secular character of the movement (Chaudhuri, 2020).

Role of Media and The Nexus of Journalism

Journalism in India has undergone a distinct transition, with rapid and populist reporting becoming increasingly common. This shift has given rise to various forms such as yellow journalism, characterized by poorly researched reporting combined with sensational headlines to boost sales, and embedded journalism, where reporters operate under the influence or control of one side during conflict.

The Indian media landscape can be divided into three categories. The first consists of outlets that promote propaganda aligned with their own ideological or material interests. The second represents the opposite extreme, committed to credibility and fact-based reporting. The former, more sensationalist category, often prioritizes stories that appeal to majority sentiment or serve political objectives, frequently sacrificing accuracy for higher Target Rating Points (TRPs). This type of journalism, described as prioritizing “sensation over sense,” has grown in strength and influence, bolstered by political patronage. As journalist Sashi Kumar, chairman of the Media Development Foundation, has observed, “Indian media is facing a huge crisis of credibility.”

Another category consists of journalism that aspires to credibility but struggles challenge the dominant populist paradigm, thereby indirectly reinforcing propaganda through cautious or muted reporting. A 2018 research report by the Human Rights Law Network, Silencing Journalists in India, documented that 75 journalists had been killed in the country since 1992 for performing their professional duties. India also ranked 12th on the Global Impunity Index in 2023, underscoring the risks faced by journalists. The restrictive legal environment further contributes to this climate. Laws such as the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act of 1974, the Information Technology Act, and provisions of the Indian Penal Code—including Section 292, Section 124A on sedition, and Section 295A—as well as the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), have collectively shaped conditions that constrain press freedom and limit the scope of critical journalism in India.

Finally, stereotyping propaganda targets particular segments of society. In India, this strategy has been central to political messaging, which have been amplified through media narratives. The sensationalization of Islamophobia illustrates this trend: conspiracy theories around the Tablighi Jamaat during the Covid-19 crisis, accusations of Muslims being “more Pakistani than Indian,” insinuations of ISIS links (particularly in Kerala), and the constant invocation of terms like jihad, halala, triple talaq, or “beef eaters” have collectively contributed to the demonization of a minority community, reinforcing ideological projects of the ruling regime. Closely connected is the appeal to prejudice, which manipulates existing social biases for political gain. Campaigns around “love jihad” or claims of a “brain drain of girls by Muslim men” tap into deeply ingrained prejudices around caste, class, and community boundaries, with the media often functioning as a political mouthpiece in perpetuating these narratives. The appeal to fear has also been another prominent tool related to stereotyping propaganda. Fear of external threats, particularly in the context of India–Pakistan relations, have become common in journalistic and political discourse, projecting the ruling leadership as a “protector” against a perceived Muslim threat. Religious polarization, deliberately emphasized through media channels, further amplifies this narrative of the leader as a messianic figure. Authority, too, has been strategically harnessed in propaganda. Politicians have increasingly turned to social media and celebrity endorsements to strengthen their influence. The Cobrapost investigation, “Operation Karaoke,” for instance, revealed how over 30 Bollywood celebrities accepted payments to promote political messages. Finally, instances of the black-and-white fallacy illustrate another common technique, where propagandists frame issues in artificially narrow terms, presenting only two choices and casting one as unacceptable. By constructing such false dilemmas, political actors simplify complex debates and manipulate public opinion (Sengupta, 2025).

The Indian Propaganda Model and Linked Economics

In the context of the following examples, it becomes evident that propaganda politics has become an integral feature of the Indian political system. Although often presented under the guise of ideology, it is rooted in manipulation and rhetorical distortion. The Indian propaganda model involves a range of actors contributing to the circulation of narratives, sustained by vast networks of money, control, and information management.

In effect, propaganda politics has evolved into an industry, where news is produced but then manipulated and disseminated through extensive communication channels, particularly social media. This industrial model of propaganda functions much like a business enterprise, structured around the generation, packaging, and distribution of persuasive messages. The process can be illustrated as follows:

Beginning with Lasswell’s Communication Model, propaganda can be understood as requiring a long-term, sustained strategy to effectively disseminate its message. This strategy, as outlined in the model above, reflects the functioning of propaganda as an institution in its own right, structured around continuity and systematic influence.

This analysis begins from the third step of Lasswell’s Communication Model, which emphasizes the role of key actors (or mediums) in the dissemination of information. In the context of propaganda, the nexus between media houses and related entities can be viewed as functioning like a business enterprise, where actors operate to maximize their own utility. For mediators, this “optimum utility” is typically reached when profit or revenue is maximized. Consequently, these actors transmit messages originating from a variety of communicators, whether political leaders or ideologically driven individuals. They then frame these messages for audiences in ways that ensure the greatest return, whether measured in financial terms or in respect to psychological influence.

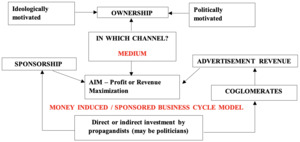

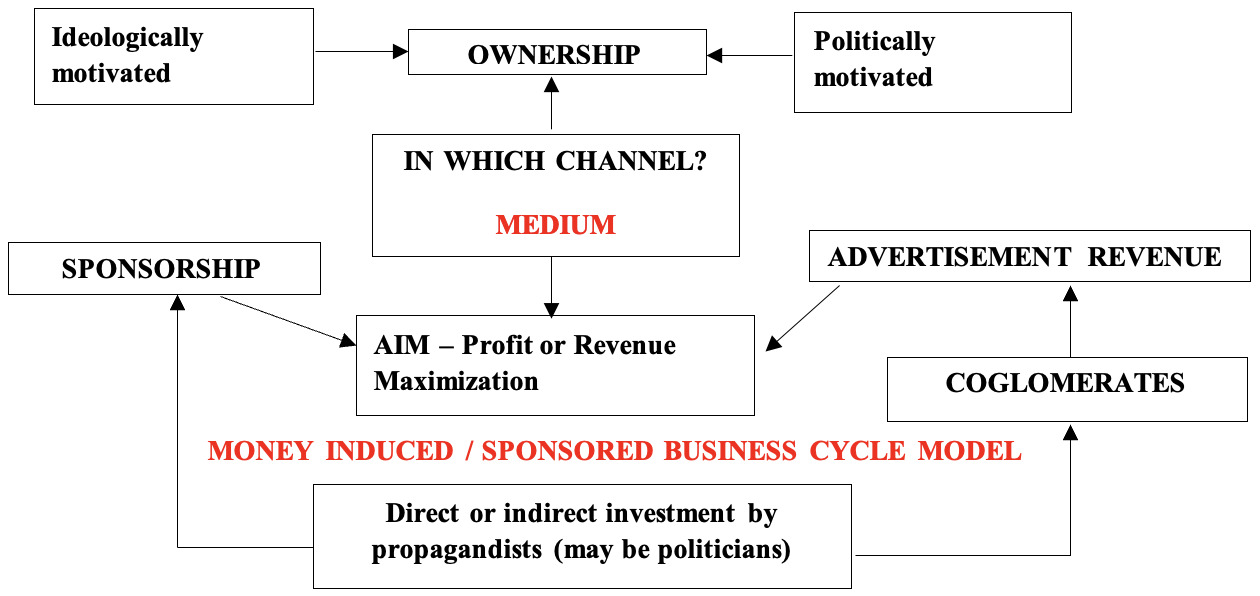

The principle of profit maximization in propaganda politics can be explained through the two filters of Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s Propaganda Model: ownership and advertising. The ownership structure of media organizations, which is shaped by political or ideological motivations, along with their sources of funding, determines their fundamental orientation. Most media outlets rely heavily on advertising revenue, which typically comes from large corporate conglomerates. These conglomerates, in turn, are frequently directly or indirectly linked to political parties or individual politicians through investments and other channels. As a result, propagandists utilize this financially dependent media to amplify their own narratives and interests.

This dynamic may be described as a money-induced or sponsored business cycle model. In economic terms, capital functions as the stock variable driving media operations, and credibility is frequently compromised within the framework of capital accumulation oriented toward revenue and profit maximization. This can be illustrated as below.

Conclusion

This paper suggests that propaganda politics has become a distinct feature of the Indian democratic system, operating parallel to formal institutions. Its steady expansion has given weight to the concern that democracy in India is experiencing a “slow death.” Propaganda now functions as an institution, shaping public perception to serve the hidden interests of political actors. The media plays a central role in this process. Whether aligning with populist ideologies or prioritizing profit over credibility, media organizations tend to amplify propaganda instead of challenging it. What emerges, then, is a cycle in which communication, economics, and ideology work together to reinforce one another. The consequences are far-reaching. Propaganda politics reshapes the relationship between state, society, and media, limiting the space for open debate and weakening democratic accountability. As India’s political system continues to evolve, the growing institutionalization of propaganda raises urgent questions about the strength of democratic norms, the independence of the press, and the direction of political discourse in the world’s largest democracy.